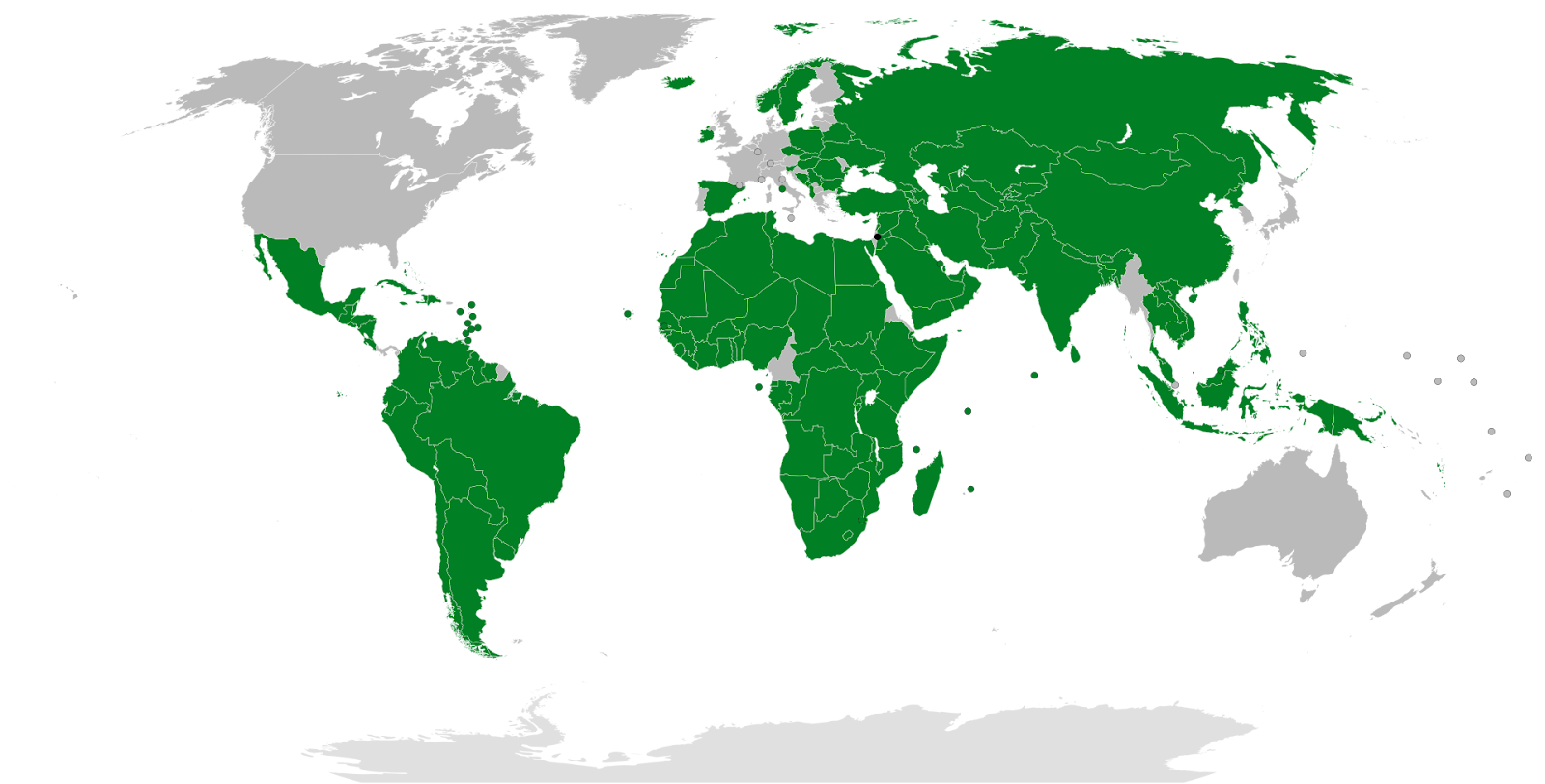

The occupation took place amidst a broader campaign for Slovenia’s recognition of Palestinian statehood. This was part of a wider initiative for Spain, Norway, Ireland and Slovenia to recognise Palestinian statehood together, sending in this way a strong collective message. On May 9th Slovenia initiated the recognition procedure. In an extraordinary session held on June 4th, the National Assembly adopted, by a vote of 52 to none, the decision to recognize the independent and sovereign State of Palestine, making Slovenia the 147th state to do so.

In an interview with “Al Jazeera”, Slovenia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Tanja Fanon noted that the voices of protest were taken into consideration by the country’s government. While the process of recognising Palestinian state would have probably been successful either way, the occupation was important to student activists both as a way to impact their universities’ political stance, and to practice political engagement. It was the students teaching their professors to not be silent in the face of unprecedented violence.

I sat down with Anja and Gaj, activists who participated in the occupation of the FSS and who continue to organize for Palestine today. We discussed how the occupation was organised, the challenges the students faced, and what a potential organiser could learn from their experience.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Justas: I was here ten years ago, in the same Faculty of Social Sciences at Ljubljana University. One of the classes I picked was Defense and Terrorism Studies. Unsurprisingly, an Israeli expert was invited to talk in one of the lectures. He told us about how it’s very hard to defeat a Palestinian because they’re not afraid to die; he was just shouting this very orientalist, racist propaganda with no other side being mentioned at all. Meanwhile, last year I heard that there was an occupation of FSS in support of Palestine. How did that happen?

Gaj: I think the idea of an occupation started even before the 7th of October, 2023. More than the Palestinian cause or any other specific issue, we imagined that occupying a faculty was an opportunity to bring a lot of people together, and to raise political awareness. Occupation can be a very important experience for molding individuals into a politically active community. It was just a matter of timing. Then, the 7th of October happened and, soon after, the intensification of the genocide. Slowly, you could see how the student organizations that are more progressive started to respond to this. It all began with Palestinian poetry readings in the Faculty of Arts in November. Then, in January, we started at FSS, once again, with reading Palestinian poetry: we have a few Palestinians in Slovenia who write poetry, so we invited them to come and read their own poems.

That was also the first time we came to FSS with specific demands in response to what was going on. The key point in the demands was to call what was happening a genocide – because that’s what it is. We also called for cutting ties with Israel. But at that point, we didn’t really have a clear understanding of the different ties the University had with Israeli institutions or our faculty.

From January onwards we started to think about how to get them to listen to us because, of course, you know, you can organize a poetry reading or a roundtable discussion — but these formats are not really going to move anybody in the leadership to act on your demands. We understood that the demand was serious and that we needed to bring more pressure to the FSS. Then we started to think more specifically about how we could do this. These actions were mainly taken within the “List of Democratic Students” (LDS). It is a grassroots student group, not connected to any institutionalized student organisations.

Essentially, we gradually started to consider that this might be the right time to act on our aspiration to launch an occupation. Over April, there were a few more cultural events concerning Palestine, which gave us some time to think through the details and a timeline of the protest.

Justas: The occupation begins on May 8th. Until then, how many people would you say were actively participating — i.e., not just contributing in the chat, but actively doing something?

Gaj: I would say it was like six or seven. We were very afraid to tell anybody about it in the beginning, because faculty occupation is a rather serious action. We kept the early stages of the process more to ourselves, mainly for security reasons. It was us and the organization meeting every other day until the end of April, when we were ready to launch the occupation. We weren’t really sure what was even going to happen, you know. We kept in mind the previous occupations in the Faculty of Arts in 2011, and a one day long occupation of a lecture hall at the FSS in 2010. We thought, ok, maybe this does not have to begin as a full-scale occupation. We decided to call a vote on this. The idea was that through direct democracy, through the assemblies, we would make the final decision on whether we occupy the faculty overnight or not.

Right before the occupation started there was a protest demanding the university to recognize that what was happening in Palestine was a genocide. Around 50 to 100 people gathered in front of FSS. In addition, just a few hours before, a right wing media propaganda outlet posted an article calling protesters Bolshevik guerrillas and members of Hamas. We also noticed that on every corner you had two police vans and that, generally, a lot of police were present in the area. This was both funny and a little bit scary: I think it was the most police I’ve seen for a long time, especially for a student organised event.

Gaj: At 2 PM, during a break, we chose the biggest lecture hall at FSS to occupy for the rest of the day. The Vice-Dean came immediately, and started asking us what was going on and what we were doing. He also told us that we cannot just disrupt a lecture of the professor who was about to resume a class there – but then we asked her, and she ended up taking our side. The professor supported our initiative, and we were invited to occupy the lecture hall. We then went on with our program, opening remarks, and an assembly for the vote. We asked the participants whether they think we should sleep at FSS – and the overwhelming majority voted to stay overnight.

Justas: Did the police react in any way as the ongoing protest moved inside FSS building?

Gaj: They couldn’t enter.

Justas: Because of university autonomy?

Gaj: Yeah, and also because the university has its own security. I always speak to the guards on my way to classes because they’re nice people to talk to. When they heard about our decision to stay overnight they were surprised, asking us what on earth was going on?… Other than that, we did not have any problems with the security, they were very supportive of our cause. It might also be a good time to mention that Slovenian public opinion surveys show that around 70% of the people support Palestinian statehood and freedom. Therefore, we could anticipate there would be some support for the occupation – but we did not necessarily expect the security to be so cooperative. They set some conditions for us, and we promised not to start any fights. We then went to the dean with our demands and explained that we will not leave until they are met. And that was it. They could not remove us.

It was also probably in the best interest of the administration to avoid controversy that would arise if the security guards fought students and somebody ended up with a broken nose. I think both sides were interested in avoiding conflict. Then, we started organising working groups within the assembly. Each of them dealt with different aspects of life during the occupation: logistics, entertainment, writing an extended list of demands not only to the FSS, but also to the university. In general, we would have 50 to 60 people present on a good day, and at least 10 when things would get more difficult.

Justas: Was there any legal retaliation? And why didn’t the dean or the administration want to involve the police?

Gaj: I think it was in the administration’s best interest to protect the public image, especially in Slovenia, where stuff like this never happens. I have not heard of any legal repercussions. We did not hide our faces, but none of us had to suffer any consequences – because it was a peaceful occupation, nobody caused any trouble. It was just a group of people sleeping in the university, and the university hesitantly accepted it because they could not do anything without risking damage to their image.

Anja: I agree, of course. I would add that maybe the response could have been different if a right wing government was in place at the time. However, in comparison to other governments, Slovenian politicians tend to be more conciliatory, to hold more progressive perspectives, even though usually these perspectives remain on a level of declarations only. It is not like there was genuine support – it was more of an effort to appease us in order to prevent further discontent.

For instance, during the protests we face almost no violence or repression. This is not because they are pro-Palestine. It’s just a political calculation. Every government since Slovenia’s independence (1991) has collaborated with Israel militarily, economically, and institutionally. To this day, Slovenia maintains a “business as usual” attitude to the Israeli state, buying its weapons and consumer goods, including those produced in the settlements. This April, the Slovenian army was involved in military drills with Israel. I think the encampment happened in a unique set of circumstances — under a left wing government and their institutional support. “Support” in a sense that, in contrast to some of the similar encampments in Europe and the US, brutal violence was not used against the protesters.

Justas: You mentioned the US – would you say there were struggles in other countries that inspired you?

Gaj: They supported our reasoning for holding an occupation. Like I said before, the idea was not new, but the circumstances were different. International occupations could be used as one of the explanations for why we’re holding ours. These events meant that we were not alone, we were not just a random, isolated 10-student group, therefore vulnerable to a repressive response and a forceful shutdown. I think the controversy around violent police clashes with the protesters in Western Europe and the US warned the university about the potential reputational damage. I, personally, almost hoped that the police would come to violently pull us out of the building on the first night because I was a little bit tired. But yeah, that didn’t happen.

Justas: Could you talk about what the people were doing during the day? The occupation lasted from May 8th to 14th.

Gaj: We tried to organise as many programs as possible, and to raise political awareness among the participants of the assembly. Not everyone had had previous experience with overt political engagement and action. Neither did everyone have an in-depth understanding of imperialism or even the conflict in Palestine itself.

We had a very productive relationship with the media. During the protest we held two press conferences. One of them was with the Dean of the faculty. We informed them three hours before, prompting in this way to show up and give a statement.

One of the working groups was responsible for gathering external and institutional support, in the form of statements from faculty, academic departments, other institutions, and some NGOs. We were fairly successful in this effort. I do believe that gathering support from the university departments was a factor important for the outcome of the occupation.

Justas: For how many students, in your best guess, this was the first political action of this kind?

Gaj: I would say for about half of the people it was their first time organizing. The key activists had plenty of previous experience. The activist community in Ljubljana is quite fractured, and this was one of the few occasions when different organizations got together. Among the people who would stay the night only a few were new to the scene. Maybe we could have done more to involve them?…

But still, for plenty of people this was the first experience of political organizing, and they went on with their own political activities because of this. I think this is one of the most important aspects of the occupation – raising political awareness and engagement. The whole occupation was also a boost for people with previous experiences of political action. It was an incredible moment in political development for everyone involved.

For many, this was also the first opportunity to participate in a protest that lasts multiple days. We’ve held plenty of protests – there is an entire joke in Slovenia about this. But such a longer duration protest was the first for many, and it ended up gathering a lot of support.

As I said before, the cause of Palestinian statehood is quite popular in Slovenia. This showed in the fact that we did not have to worry about food. 20 pizzas were paid for and delivered directly to FSS every day. We still don’t know who did this for us. This was a really nice moment and a real boost of morale to receive such support from the outside.

Prie GPB veiklos galite prisidėti čia

Ačiū!

Justas: What else would you say is needed to organize an action like this?

Anja: I think including Palestinian voices was really important for the legitimacy of the encampment. Palestinian people were involved in the entire process. We were doing all of this for them; it was them we stood in solidarity with. I think this is one of the most important things you have to do when organizing something connected to the Palestinian struggle.

Gaj: And this also ended up raising a lot of support from the Palestinian community here, which I think was very, very important. If you’re organizing and don’t have the support of the Palestinian community – you’re doing something wrong.

Justas: So what was the outcome of the occupation?

Gaj: The main demand was that FSS releases a statement naming what is happening in Palestine a genocide. Any such statement has to be approved by the Senate, so we ended up at the Senate hearing. We wanted to allow the student radio in, and the national media also wanted to participate – but this was blocked. After the discussion, more than half of the departments in FSS ended up supporting the demands. The statement was accepted the way we drafted it – no changes were made.

In a bit of self-criticism, I must admit that maybe some of these demands were not well thought through. At one point we ended up having the rector at one of the assemblies. We talked with him. We went through the demands, and he just kept rejecting them: no, we can’t do this and we can’t do that. We only can recommend the state to do something. One of the demands was to start a fund for Palestinian students who came to Slovenia in order to provide the accommodation and a small stipend, as it was done with the Ukrainian students.

Justas: Did they recommend it to establish this fund to the state?

Anja: I think the University Senate put out a statement calling on the government to create such a fund.

Gaj: Regarding the outcomes – apparently our Minister of Foreign Affairs told “Al Jazeera” that the occupation was one of the incentives for Slovenia to recognize Palestinian statehood.

Justas: Could you just give us the timeline of the events of the occupation and the recognition of Palestinian statehood?

Gaj: So our occupation started on May 8th. On the 9th of May the government initiated the procedure for the recognition of Palestinian statehood. It was finalized on May 30th.

I also just had a conversation with one of my comrades. She said that a few of her professors wouldn’t call what is happening in Palestine a genocide – but that changed after the occupation. They changed how they speak about this issue. Overall, I think that’s probably one of the more important outcomes.

Justas: What would your final thoughts and recommendations for anyone thinking about such an action be?

Gaj: Preparation is the most important part. Maybe don’t organise an occupation in two weeks. Decide what working groups you will need for logistics. Plan a program not just for the first day, so you don’t end up planning everything the night before. I think we could have had more educational activities. Along with the demands, they are the most important part of occupations like this. I see occupations like this as a setting for education, as a chance to raise political awareness, encourage political development, and build organizations.

Anja: My suggestion would be to connect with as many collectives as possible before organizing such an action. Include various voices in your movement. Include democratic media in your organization, so you can control your narrative and receive the most objective reporting from a decolonial perspective. I think this was lacking in our media discourse.

Where motivation is concerned, I would encourage you to never doubt your convictions, goals and values. If we don’t push against the forces normalizing fascism – it will only get worse. Stopping, giving up is not an option.

Stand in solidarity with the oppressed people, include them as the primary voice in everything you do – only then your political work will be useful.

Taip pat skaitykite

-

Palestinos vėliava Nidos pušynuose ir dvigubi standartai žodžio laisvei. Pokalbis su Nidos meno kolonijos direktore Egija Inzule

-

“In Slovakia the whole process is the same as in Hungary and Poland, but like on steroids, it’s much faster”. Interview with Tomáš Hučko

-

Ar kurjeriai bus įdarbinti? Austrijos atvejis

-

Išsamiai apie pensijas ir II-osios pensijų pakopos problemas su Romu Lazutka

-

Amazon – kaip vėžys, augantis žlugusios Lenkijos pramonės vietoje (2 dalis)