[šis tekstas – anglų kalba; lietuviškai jį paskaityti galite čia]

“We lost our homes! In terms of experience and morality, Prague is totally declining. There are no politicians who think about the future (which we don’t have anymore), they just count money…”, says one of the contributors of the journal, issued by the Prague self-organized initiative Bearable Living that fights against AirBnB.

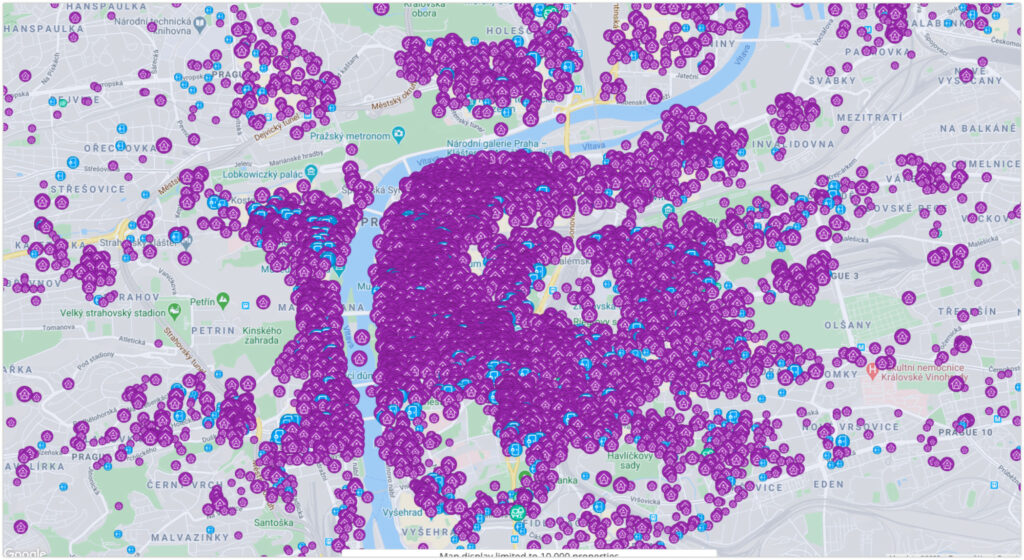

The journal tells stories of people who live in the so-called “hotels in residential houses”: buildings where the majority of flats no longer serve the purpose of long-term housing, but short-term rentals, mainly for foreign tourists. Before the COVID pandemic, there were more than 15,000 flats on the AirBnB webpage, which could house around 40,000 local people.

The stories might seem funny to the reader. However, if one imagines that this is the everyday reality that happens in the place that is supposed to be the most secure – home – these stories do not seem so funny anymore. Another woman from the city center describes her experience:

I cannot sleep in my bedroom for the time being. It is not possible because of the noise… I am not calling the police anymore, because it means I won’t sleep at night at all… Now I sleep in the kitchen, but only when the tourists are not here, which means on weekends and during the week sometimes. When it is unbearably noisy, I sleep in the corridor, on the carpet on the floor. Usually, I get some sleep three days per week. I started to leave my family and to go to sleep in another apartment, but that does not help much, because it is also in the Prague city center.

Some British guys were accommodated here a few days ago. Some of them came home around midnight and some around 4 a.m. They could not come inside the house, because they were too drunk, so they were shouting and kicking the doors. While I was calling the owner, one of those guys slided to the terrace from the roof. Apparently, he climbed the ladder to the roof and if he had made one wrong step, he would have been dead by now.

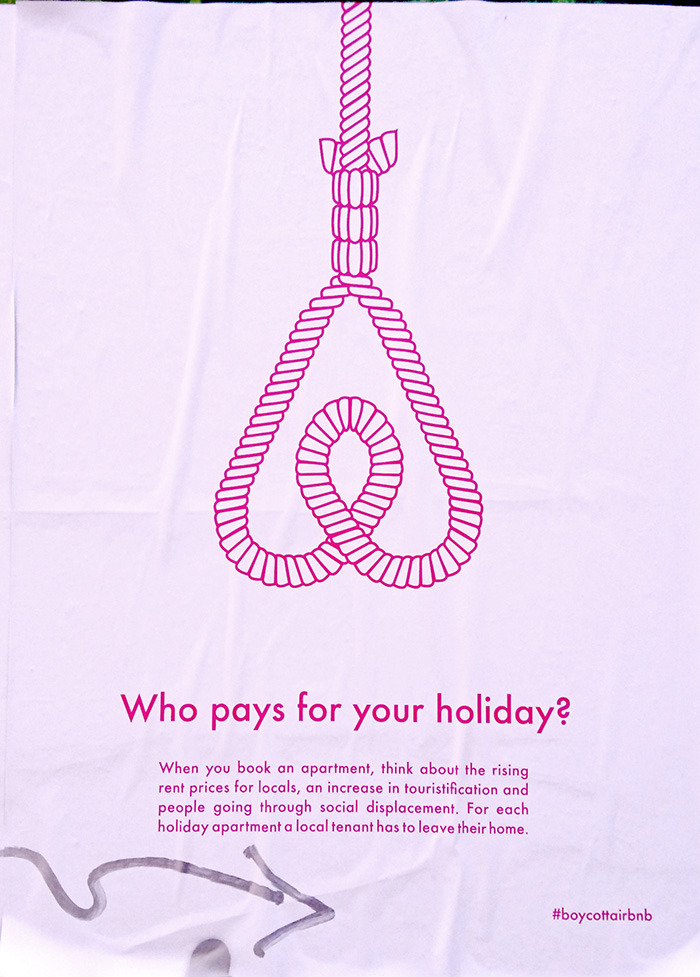

Public urination, vandalism, climbing the roofs, partying on the terraces in penis costumes, throwing things out of the windows, stealing, making fun of the local dwellers, and sleeping in the corridors have become everyday experiences for those living in the AirBnB hotels. As an act of resistance, the locals usually call the police and try to persuade the drunk tourists to behave themselves. However, obviously, it is not enough. To protect their homes, the locals of Prague 1 (the old town) and other districts affected by AirBnB started a political fight. According to them, AirBnB should be banned and evicted from the city, and flats should serve the function of long-term housing instead of unregulated business.

This hatred towards AirBnB is not unique. In many cities around the world, people and municipalities are trying to impose control measures on short-term rentals. However, AirBnB is not only about short-term rentals anymore. It became a symbol of the transformation of housing into a mere commodity. It is an obvious proof of how the capitalist economic logic functions in the city: housing is for sale, not for fulfilling human needs. Those who can afford it, can live; those who cannot, must leave to the outskirts.

Cities like Barcelona, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, and others have already issued regulations of the platform. In reaction, AirBnB came up with a novel tactic: it started to organize a social movement for deregulation, using the methods of late community activist and political scientist Saul Alinsky. The platform is using a weapon that was invented by left-wing movements and trade unions exactly for the purpose of fighting businesses that act as parasites of human needs. And, in contrast with the small initiatives like Bearable Living, AirBnB has money, know-how, best campaigners, media and lobbying specialists, and trained persuasive staff. Here’s a question for all of us: how do we resist the commodification of cities when democratic means of fighting, that used to belong to the people, are now in the hands of the investors?

AirBnB movement for deregulation: how a battle for democracy became a domain of the rich

The new strategy of legitimization, used by AirBnB, is described in a report of Luke Yates, a sociologist from the University of Manchester. Mainly, it is the corporations’ ability to “influence [the] democratic institutions by creating and coordinating apparently independent social movements to act on their behalf”. AirBnB uses coordinated groups of small unprofessional owners and the public image of small entrepreneurs. The goal is to protect the interests of those about whom the platform really cares: the big investors.

The strategy is based on a network of “home sharing clubs”. With the platform’s support, these clubs lobby local politicians for (de)regulation. The platform supports the clubs by helping with organizational issues and having AirBnB employees personally take part in the owners’ protests. Platform employees provide political education (in a neoliberal vein), create stories for the media, and draft the policies that the owners lobby for. It is worth noting that there are some home sharing clubs that refuse to be supported by the platform, but AirBnB employees consider these clubs a failure. The report states that there are 350–400 such clubs globally, 40% of them – in the USA. Each club has up to nine members.

The clubs are much more sophisticated in campaigning than the local citizens. For example, the clubs in San Francisco spent 8 million dollars opposing the attempts of regulations, hired campaigners from the Obama campaign, made 32,000 calls to 6,500 landlords, and persuaded several hundred of them to attend court hearings and protests (compare it to the capacity of any urban movement in your city). AirBnB’s Global Head of Policy and Public Affairs Chris Lehane (former political advisor to Bill Clinton and Al Gore) considered this campaign so successful that he wanted to replicate the San Francisco model around the world.

What does the organizing process look like? AirBnB employs community organizers to look for appropriate owners. They usually own only one property and are, preferably, small entrepreneurs working in the sphere of culture. Ethnically diverse local patriots who ideally lived through a traumatizing experience and whose main source of income is AirBnB are the ones selected for the home sharing clubs. The motto is “local, precarious, and diverse”. Yates cites one of the AirBnB employees, Manny from the UK, who explains the logic behind such selection:

So when you have like local councillors and people out there saying ‘Oh AirBnB’s terrible’, you have these hosts who become the face of campaigns and become the face of the mobilisation movement, going ‘No, I’m just Dan from Leith and I just need to make a little bit of income’, or ‘I got laid off from my job’, or ‘I have a health problem’, and you kind of tease out these people

After initial selection, the first meeting happens. The first one-to-one conversation between a community organizer and an owner takes place in an AirBnB office. Just like in the classic process of organizing, the owner receives a small motivational task (signing a petition, etc.) The second meeting usually happens at the owner’s home, where s/he feels comfortable. The goal of this meeting is to establish a trustful relationship. The corporate organizer tries to figure out whether the owner’s story is compatible with the desired public narrative of AirBnB. Further meetings with other owners that aim to build personal relationships follow. The goal is to find trustful local leaders, who will be able to coordinate home sharing clubs in fights for deregulation.

The problematic aspect of grassroots corporate lobbying is the absolute absence of transparency. The platform publicly claims that it has nothing to do with the home sharing clubs. This means that the public and politicians might not know that this is not an expression of the small owners’ democratic will, but a corporate strategy with a clear business goal.

Meanwhile, AirBnB is a platform that repeatedly refuses to cooperate with the public sector (mainly, regarding the provision of data). In some countries, like Czech Republic, it violates several regulations: mainly, Construction and Trade Law by using the flats that are supposed to serve as long-term accommodation for its business. Obviously, its activities have nothing to do with democracy. On the contrary, the platform abuses strategies and tactics of social movements for asocial purposes. In the long run, they enforce gentrification, lead to unaffordable housing, deterioration of local communities and neighborhoods, and, often, to insecurity or even moving away.

Yates also claims that other platforms, such as Uber or Lyft, are interested in the strategies of social movements. Thus, we can expect an expansion of corporate creativity and even higher risks for democracy. Moreover, these tendencies lead to the weakening of trust in democratic processes and meaningful political participation.

Strong cities as a weapon of the nowadays Left

As the current political reality shows, cities, and not states that are closely intertwined with the capitalist economy, are able to fight the much stronger neoliberal forces. They introduce progressive policies for which the states lack courage. It comes as no surprise that cities, and not states, lead the struggle against financialization of housing and commodification of urban space, and create new sustainable ecological models and social policies that fulfill the needs of local citizens. The struggle against AirBnB is not an exception from this logic.

The movement of the cities, which is also called new municipalism, is based on the population’s awareness of local topics and on close ties between politicians and citizens on the municipality level. Geographical proximity and personal ties between city dwellers also play a role. Municipalist movements like the famous Barcelona en Comú base their power and legitimacy on this proximity. This platform in Barcelona has been active since 2014 in pushing for principles of social justice (including the rights for housing and healthcare), socially and ecologically sustainable economies, democratization of municipal political institutions, and ethical responsibility of politicians expressed in a pay cap, transparency or avoidance of loans from institutions that generate debts.

In the very beginning of its existence, this movement was based on public assemblies, during which the politics was made on the streets, without representatives or official institutions. The current mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau, comes from the PAH (Platform for People Affected by Mortgages), where she was an active speaker for years.

Another successful movement is Zagreb je naš (“Zagreb Is Ours”), which recently won the municipal election in the Croatian capital. It also has roots in the politics of social movements and urban struggles. It grew from the Pravo na Grad (“Right to the City”) platform that fights against privatization of public spaces and overxploitation of urban space in general and for collective management of public goods. One of the famous struggles of the platform was campaigning for the public space in the center of Zagreb (the We Won’t Give Away Varšavska Street campaign), and against the destruction of the Kamensko textile factory.

The platform and the movement are also examples of how a horizontal grassroots structure and a more professionalized organizational form could co-exist, be flexible and shapeshifting, depending on circumstances and goals. Such organizational flexibility contradicts the path of professionalization and bureaucratization of grassroots movements, common in Central and Eastern Europe.

Backlash: concentration of power on the state level and limitations of activist scene

While new municipalist movements with the iconic Barcelona en Comú are an actor that strives to give cities to the people, and not to capital, not all countries present a fertile ground for them.

In Prague, as in the whole Czech Republic, the neoliberal state housing politics (privatization and deregulation of the housing market) gradually led to the current severe housing crisis. Affordability of housing in Prague is one of the worst in Europe: one must save 14 annual payments to buy a flat, which is more than in Munich, Berlin, or Vienna. Paying 1/3 (or even more for vulnerable low-income households) of monthly income for rent became normal.

73% of the 15,000 listings on AirBnB are for commercial use (rented more than 90 days per year or owned by investors having more than one property). However, issuing a regulation of AirBnB took years. How is it possible? There are two main obstacles: centralization of power over property regulations on the state level and inefficient pressure of urban movements.

Municipalist movements like Barcelona en Comú or Zagreb je naš proved to be strong enough to fight uneven urban developments. However, we must take into account that, in different countries, there are different political cultures that influence institutional, legal and political possibilities of city governance. Cities cannot do progressive politics when they lack minimal institutional and legal means to do so.

This is the case of Prague. While other European cities can issue a regulation of AirBnB, Prague has no legislative power to do so. And while necessary laws were proposed to the parliament, they were never discussed by the state politicians. Not only regulation of the short-term rentals, but the housing question in general cannot be solved on the city level. Besides legislation, this is also because the municipalities sold the major part of their property in the 1990s and, in the capitalist universe, where the property owners dictate the rules, they do not have any real power.

A further step towards the centralization of power was made by the new Construction Law, which took the right of giving construction permits from the municipalities and transferred it to state departments. While experiences from many European cities show the benefits of strong municipalities for progressive politics, Prague remains on the periphery of those tendencies and only now tries to put very modest limits on the developers’ power and acquire property .

Secondly, as all of us know, politicians never do anything if they are not pushed by the citizens, movements, and initiatives. In Prague, there are two main initiatives that have chosen two distinct strategies. These two examples raise a question about the general strategy of urban movements: legal or radical?

The first initiative is a self-organized group of flat owners: Bearable Living in the Prague City Center. Besides other things, it publishes a journal, where citizens write their stories, one of which is cited at the beginning of this article. The initiative strives for enforcement of a particular legal apparatus and mainly does political lobbying. In this legal fight, the initiative was successful: finally, there is a court verdict that AirBnB is a business activity and, thus, is a subject to taxes and other regulations (e.g., it is required to have a clear visual sign on a building with AirBnB flats, stating the business owner name; renters must pay contributions to the health and social insurance which are not applicable for long-term rent providers).

However, re-telling the story of AirBnB in the language of law extracts the political conflict that lies at the core of this problem: the conflict between big capital turning housing into a financial asset and the well-being of the local people using their flats for what they were built for—living. The flat owners living in the city center are of the middle or even upper class and are far away from articulating the general anti-capitalist narrative and criticizing the economic logic that underlies the problem they are fighting against. Will a “proper” legal category transform 15,000 flats into secure housing? Hardly. The above mentioned court verdict makes it harder for AirBnB to turn a profit, but so far it just proposes a legal way of doing it, instead of making a meaningful change towards bringing flats from the short-term to the long-term housing market.

Another initiative is the radical-left Stop AirBnB, which is famous for its direct action, which received unprecedented media attention. Activists rented an AirBnB flat and organized a public exhibition about the platform there, as well as workshops, concerts, and an urban intervention: a 12-meter long banner on a historical tower in downtown Prague. The action was attended by the city mayor and local citizens affected by AirBnB. In comparison with the legalistic language, it proposed a coherent and attractive narrative: the city is for living, not for sale. However, the activists fell into the trap of putting too much emphasis on direct actions instead of strategic politics: after this one direct action, the initiative dissolved. And when the moderate wing of urban resistance needed help with the media narrative, contacts of journalists, and public attention, the radical left was not there.

Due to the pandemic, many AirBnBs went to the long-term market, which (besides other things) led to a rent decrease of 10 percent. It is obvious that, when it comes to protecting homes, the virus was much more efficient than the politicians. The general decrease gave a rise to small individual victories of the tenants, who were asking for a rent decrease due to the pandemic, and in many cases were successful (including the author of this article). However, neither the virus nor individualized solutions present a path towards systemic change. By pointing out the illegality of AirBnB, the local initiatives apparently just created a need to legalize it, and not to ban it. While, for now, the path of legal short-term rentals is clear, the regulation is still not on the table and Prague still does not have the legislative power to issue it.

Cover photo: courtesy of Harvard Business Review

Taip pat skaitykite

-

The Interview: How to Occupy a University? The pro-Palestine Student Occupation of Ljubljana University

-

“In Slovakia the whole process is the same as in Hungary and Poland, but like on steroids, it’s much faster”. Interview with Tomáš Hučko

-

„ChatGPB and a half“: Qassem from Gaza – „You don’t destroy political thought by weapons”

-

Challenges of healthcare reform in Ukraine: on workers’ perspectives and struggles

-

Ian Parker: The Psy Professions, Pathology and Alternatives

Sena kaip pasaulis problema – kaip išsaugoti vietinę rinką nuo galingesnio užsienio kapitalo. Analogiška problema galėtų būti mokslas Lietuvoje – juodaodžiai, indai ir kiti užsieniečiai nusiperka mūsų šalies diplomą ir įgūdžius pigiau negu kitur ir taip mes savo mokesčiais dalinai padengiame svetimšalių plėtrą, savo darbo saskaita.

Labai keista, kad straipsnyje nė kiek neužsimenama apie tai, kad Prahos municipalinėje taryboje daugumą turi Piratų partija kartu su iš aktyvistų kilusia Praha sobě (Praha pati sau (?)) ir centro dešinės koalicija iš TOP 09 ir krikščionių demokratų, o meras, atstovaujantis Piratus siūlė apmokestinti nenaudojamą nekilnojamą turtą pagal sunaudojamą energiją. Tai kažkaip keista kad pateikia Barselonos ir Zagrebo pavyzdžius, ir nors panašūs judėjimai laimėjo Prahoje (ir tai simbolizuoja pokyčius, kadangi tradiciškai Prahą valdė konservatoriai), autorė koncentruojasi tik ties aktyvistais kurie užsiima Airbnb – nors laukas gerokai platesnis ir įtraukia tiek daugiau NVO, tiek ir Prahos planavimo institutą, tiek savivaldybę.

Na straipsnis, kaip galim matyt, gavosi jau ir taip netrumpas. Veikiausiai reikia kažkokias ribas temai uždėti. Bet jei manot, kad yra dar kažkas (kokia nors gretima tema ar akcentai), ką būtų verta paminėti ar pristatyti, parašykit GPB. 🙂