(Šis tekstas – anglų kalba. Jis jau verčiamas į lietuvių ir lietuviškai mūsų portale pasirodys netrukus)

What is driving double-digit inflation in the Baltics? How valid is the often-heard argument that further wage increases for workers will only fuel inflation further? Wealth taxes are deflationary and are an appropriate tool to tame inflation. Yet, how can we defend these taxes against the „financial experts”, as well as the defenders of the mythical rich grannies living in Vilnius old town? And when we win, what should be done with the money collected from these higher taxes? The European Central Bank is raising interest rates to fight soaring inflation. In the short term, this shock therapy for the economy may help to reduce inflation. However, do the short-term benefits justify the increased indebtedness of the population that goes with these measures? What can we learn from past crises in the fight against inflation and the cost of living crisis? Finally, why have all the successful countries tended to deliberately distort the market in one way or another and… how Japan set up its first analytical center called the Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books.

On these and other topics, GPB interviewed Jeffrey Sommers, professor of political economy and public policy at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (USA) in Lithuania last November. He has been interested in the Baltic countries since his arrival in Latvia in 1995 and is a Visiting Professor at the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga. During his stay in Lithuania, J. Sommers participated in the inaugural international conference „Tackling the Rising Cost of Living: Towards a Progressive Approach for the Baltic Countries” organized by the Solidarity Institute of the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party on 3-4 November last year.

What factors, in your view, are the major drivers of inflation in the Baltic region? Would you agree with those who argue that rising wages is one of the main contributors?

We see that kind of discourse the world over and, to some extent, we could say that government support during COVID played some role in this crisis. But that’s not the only thing by any stretch. In terms of the start of inflation, it really began with COVID, the disruption of all these delicate supply chains where any interruption can cause big problems. And because people were at home, they stopped consuming services and increased their consumption of goods.

And at the same time you had supply chains disrupted throughout East and Southeast Asia, which generated inflation. Now, the inflation has been sustained by that and we still have some smaller number of supply chain issues, they are not entirely gone. But it’s really energy and the war – that’s the big one. But, Europe’s warm winter is helping to drive inflation down.

So we have some economists like Larry Summers who argued very early on that we risk creating a wage-price spiral that would be inflationary. I don’t want to completely discount that, but it’s more of a 1970s-like situation where we see these big commodity price spikes that are fueling inflation. Not that other issues don’t come into play at all, but it’s metals, food, it’s of course oil and gas, that has recently been the problem, and depending on factors such as unpredictable turns in the war, weather, and the evolution of the COVID virus, could become so again.

And then you might even have some role of the demand that’s been generated by the deployment of NATO forces here and the rest of the region along Ukraine – that could be a factor as well, because the inflation is at its highest in Moldova and the Baltic states where energy was purchased on short-term spot price contracts, thus seeing the steepest price increases in autumn 2022.

So it’s very specific. And this thing about governments’ support and inflation – take a look at Finland. Their inflation rate is 6% and they’re just right adjacent to Estonia, so I don’t buy that argument that it’s just wages, because it doesn’t come into play in some of these other countries.

Riga. Author: Diego Delso

Are there any factors that are specific to the Baltic states?

The thing for a long time you had in the Baltic states was that wages were not really keeping up with productivity. And then they started to go up faster than productivity. So some of that was just [prices] catching up with wages that hadn’t gone up previously. So it is true that wages were rising faster than productivity for a while, but some of that was just making up for that lack of wage growth earlier.

And then the other issue is property prices. This is an old problem in the Baltics. I was publishing articles with my old friend Michael Hudson here as early as 2004-2005, stating that you were having a huge housing bubble fueled by all this Scandinavian money pouring into your banking sector, jacking up the prices. We tried asking people just very simply: how can you look at the current income profiles of your citizens and where they’re projected to go, and then look at the housing prices. How is this ever going to be serviceable? No one cared much. They were making too much money on the commissions from selling properties. So we have this ongoing problem. The only way you can really fix that – and people may not like this message – is by increasing property taxes.

That’s exactly my next question: would taxing real estate and introducing general progressive taxation be appropriate measures to fight inflation? This may be an unpopular solution, but what is your take on this?

This is a matter of eating your vegetables and taking your medicine. People don’t like it, but it has to be done. You can’t continue to eat cotton candy and chocolate bars every day and expect everything to be fine.I’m not suggesting just raising any and all taxes, but taxes by their very nature are deflationary. So if you’re in an inflationary environment, one of things you can do is raise taxes. Not on food, that’s the big question, because all taxes are to some extent zero sum, but on high-value properties, yes.

The best way to do it is to create value from those taxes, to do something that actually generates more wealth and efficiency later on. But the reason that you must to have property taxes, which are a feature of all modern economies, is that otherwise you have to tax income at higher levels. And if you tax income, you’re hurting working people too much. So if you want to reduce the tax burden on working people, you have to increase the tax on property. And again, it can be progressive, and doesn’t have to hit working people.

if you want to reduce the tax burden on working people, you have to increase the tax on property

But the other thing that property taxes do is take housing prices down. Every family, every household has a certain amount of money for housing – that’s the money they have for it and they won’t have more. And somebody is going to get that money. It’s either going to the state, in part through taxation, and will be used for kindergartens, healthcare, national defense, paving roads, all these things that are actually productive and help people and the economy. Or it can go to banks. As the property tax goes down, the housing price goes up because there’s more money available for the purchase of a property. Banks love that, because that means larger mortgages, larger fees, larger commissions and more debt service payments.

The argument that you’ll get from the banks and the real estate sector as to why this is a bad idea is that they’re protecting grandma. Suddenly, they’re very concerned about this vulnerable population of elderly people on pensions. They’ll tell you about grandma who inherited from the pre-Soviet period 160-square-meter apartment in central Vilnius and if you increase her property taxes, you’re kicking her out onto the street. Now, never mind that there are maybe three women who meet this description in the entire country – and we can protect those three grandmas, actually, by collecting this tax after she dies, from whoever inherits that 600,000-euro apartment and can afford to pay the tax. So that’s just a false argument. Liberals are trying to confuse working people, saying the Social Democrats are trying to increase your property taxes and kick grandma to the curb.

But there will be losers in this. The banks lose, which is good, because then there’s money for other stuff that’s more important. And the real estate sector loses. And there are some people who just got plain lucky through the lottery of history that found themselves coming into some very valuable properties. And granted, they’ll pay more and will not continue to see this crazy increase in prices. But what they get in return is fewer financial crises and a more stable economy and society.

You need to have a more modern structure for your property taxes. […] Debt service payments cannot be sustained at the level needed to sustain these prices. The resources need to be redirected into the rest of the economy.

In response to inflation, the European Central Bank has raised interest rates. It also launched a new transmission protection instrument to quell bond strength and calm down the financial markets. Are these measures adequate to achieve the stated goals?

They’re short-term for the most part. Just the general raising of interest rates, of course, is deflationary, and so it does work.

..in the short term?

It depends. If you want to keep them up, this will continue to work by harming the economy, which is deflationary. We saw this before in the US under the late Carter administration or early Reagan administration. Paul Volcker, who was the head of our Federal Reserve board, carried out his monetary shock. We had big inflation and so he kicked up interest rates, which led to 18–19% mortgage rates. That solved inflation, but it did so by throwing huge numbers of people out of work. It created a recession not only in the US, but also in the whole world. And then, because other countries held lots of debt in US dollars, it created a global debt crisis which lasted 20 years.

So the costs were massive. The ECB doesn’t have a lot of tools at their disposal. Choking the construction sector – which is what the bank is doing, because it’s related to so many other sectors – is a way to slow down the economy and dampen demand and this way bring wages down. But ultimately they’ll have to solve the commodity price inflation, which is the ultimate source of inflation. Just as it was in the 1970s, when they also blamed it on labor. But the independent variable, the thing that was different in the 1970s from 1950s and 1960s, was this big energy price spike which then led to price spikes in food and minerals. And so in many ways it’s similar to our experience now.

Cloudy ECB. Author: Patrick Stoll

Some people say that we are in a unique situation and old models do not necessarily apply.

Yes and no. The old situation [in the 1970s] was a result of the assertion of power by formerly colonized parts of the world. OPEC – the Organization for the Petroleum Exporting Countries – discovered their power with the 1973 Yom Kippur War and that they could punish the countries that were supporting Israel by just slightly turning down oil production, which they did. This resulted in a 300% spike in oil prices. And then they got it in their heads that why stop there? This works great.

And so Iran, who was the United States’ ally, stated: you’ve been taking our oil, making all sorts of petrochemicals and selling it to us at 1,000% more than the underlying commodity. We think we should be able to do this as well and so we are going to. That’s what Iran said and did and the costs to our economies were massive. You must remember that at that time our economies were about 50% less fuel efficient than they are now and we were not producing all that much oil or gas.

And the way it was addressed, again, was this tremendous monetary shock that Paul Volcker launched. But then other deals were made. We had close relations with the Saudis because they made a fortune from this energy windfall. They didn’t know what to do with the money, they did not have banks that could handle it. So they were sending the money to New York and London banks just trying to find ways of doing something with this money. And then Henry Kissinger had a brilliant solution to their problem. […] He said to the Saudis: look at the world, it’s really a mess, we’ve got all these suffering people, former colonies make all these crazy demands. But look at the United States who got this huge ocean on one side, this huge ocean on the other side, you’re not going to find a safer place than putting your money in US Treasury bills. Just buy our debt. And to keep that investment even more safe, you price your oil to everyone else in dollars. If everyone else is going to buy dollars, that will make your Treasury bill investment even safer.

So they started doing that. That made the US dollar the global reserve currency and the country started getting huge benefits from this. The next step was related to this new tight relationship between the US and Saudis. The US (the National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter specifically, Zbigniew Brzezinski, wanted to bait the Soviet Union into invading Afghanistan. This was, in Brzezinski’s words later, to “give them their own Vietnam.” As our then national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski was a very big Polish nationalist, who was essentially running his own foreign policy against the Soviet Union.

The US then got the Saudis to turn oil production up in the mid 1980s and bring the prices down in order to hit the Soviets, because their economy was stagnating and they were becoming more and more dependent on oil exports. In 1970, the Soviets had thought they were rich because of the increase in oil prices and they’d gone on this big arms buying binge and thought it was always going to be this way. But Brzezinski brought the oil down to $10 a barrel. That was great for the United States economy – it brought cheap energy again and everyone needed to use US dollars to buy oil. Saudis were the biggest exporter of oil and that meant that they could more or less set or determine the currency that oil would be traded in.

All this gave the United States this great run that’s lasted all the way up until now. The geographer David Harvey referenced this as the spatial fix to the 1970s crisis. And by that he meant that we incorporated more and more of the world’s resources and labor into global chains of production and consumption.

One big part of it was the 1990s break-up of the Soviet Union. We were happy with that because we got a class of oligarchs that wanted to sell whatever they could get their hands on: anything from oil to pieces of brass that some guy in the middle of the night at a cemetery with a flashlight would rip off of a headstone take to Klaipėda, put it on a ship and send to the US or Germany. Lots of commodities were flying out on the global markets and that worked great to keep commodity prices down.

There is no new system we have in place and, just as in the 1970s, we’ll have to experiment and see what comes out of that experimentation. We don’t know yet.

And then you have the Deng Xiaoping reforms in China. Deng knew that they had to restructure the Maoist economy. He went to the United States in 1977, visited some factories and was very pleased with what he saw. He didn’t know that he was seeing the very end of American manufacturing, but it looked super efficient, exactly what China needed at the time. So they launched reforms, which over the course of 30 years brought hundreds of millions of dirt-poor Chinese laborers into what we sometimes in Marxist language call the global reserve army of labor, into the global labor market. So they’re all now producing stuff and all this stuff is super deflationary.

But now we see that China is reaching the limits of this growth model and becoming a middle-income country. All the peasants are gone from the countryside, except the few that are left to do farming. And with the former Soviet Union, the cheap commodity party is over. The war makes the situation even worse. There is no new system we have in place and, just as in the 1970s, we’ll have to experiment and see what comes out of that experimentation. We don’t know yet.

Aside from the ECB’s interventions, what should governments do in their own capacity to prevent an increase in poverty and economic imbalance nationally?

Again, the property tax, because that will bring housing prices down, which is good. But I would definitely increase the non-taxable minimum threshold, the level at which you begin taxing wealthier people. Additionally, finding as many possible ways of provisioning public services that consume as few inputs as possible.

You have to feed people anyway. You don’t want them dying on the street, although there are a few neoliberals who will be all down for that program. You can put more people to work in day-cares, kindergartens, etc. Additionally, we’re going to have to find a new energy paradigm. In this context, conservation is important. Anything we can do to better insulate buildings using locally produced materials is important. But this is going to be tough as long as we have this commodity price inflation.

Thinking about ways at the national level, re-balancing the tax code and trying to avoid or conserve as much as possible those commodity inputs that are at a high price. If the Ukraine war ends up being short, then you can have big state interventions. It will be short-term and the inflationary effects would be short-lived. But if this war and its impact on energy and commodities generally is long-lasting, then we must think in different ways altogether.

This brings me to my next question. How do institutional structures need to be rearranged to ensure a more sustainable development of European economies in the long term?

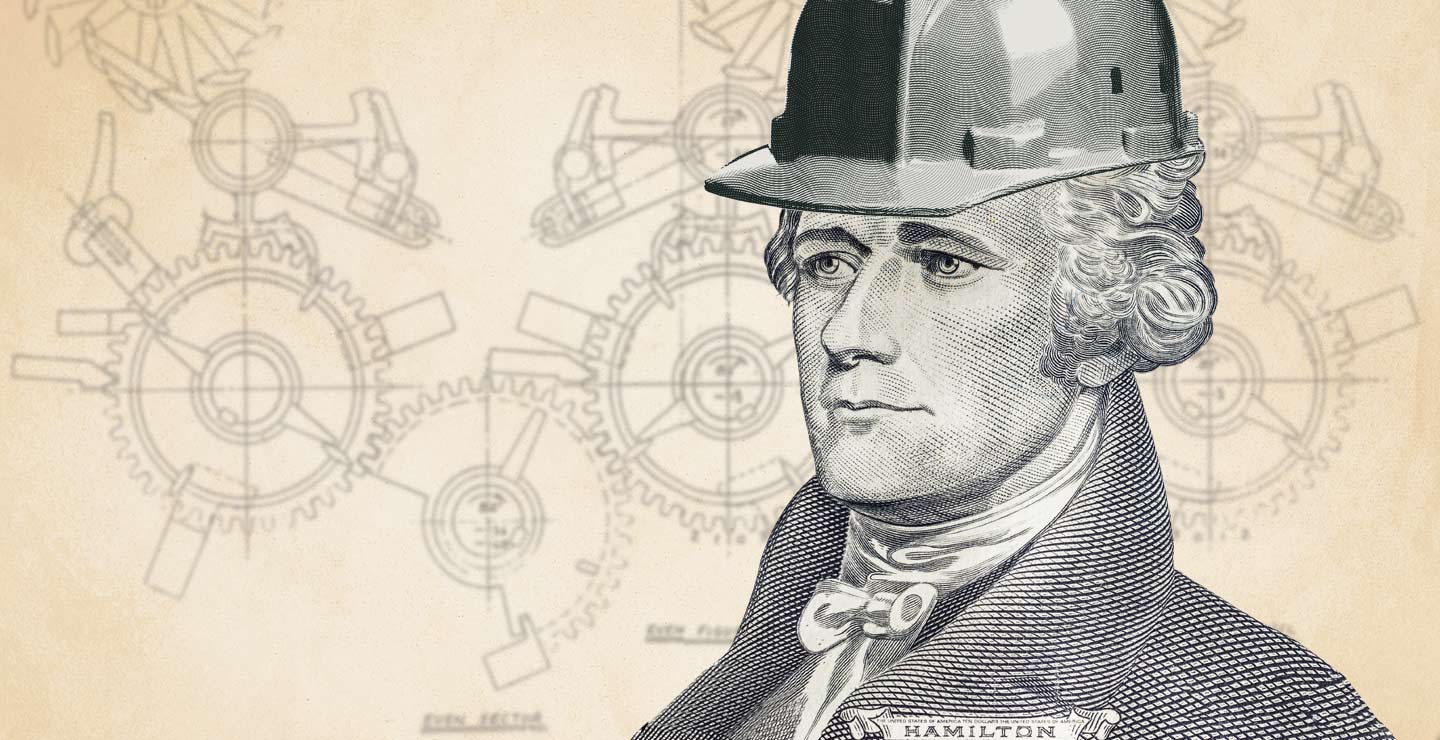

One way relates to the so-called Hamiltonian moment. Alexander Hamilton was the first US secretary of the Treasury. What he did to deal with all the wartime debts from our Revolutionary War was to write them off the books of individual states and have the federal government take the debts over. He did that not because he was a nice guy, but because he wanted the US to be creditworthy going forward, since he knew that it would be a credit-hungry nation as it developed. And it was effective.

And so one could think of ways of wiping out some of the debts accumulated by various EU countries. We already know where the opposition will come from: not just the banks but the Germans too. However, one reason we have a lot of these debts is because of the euro, frankly. You have areas which all of a sudden found themselves with a currency that was much overvalued, which meant that their exports were now noncompetitive. For instance, Italy, a country that was growing strongly between 1960s and 1990. They had some problems, but when they adopted the euro that really threw them off. France, Spain and Greece as well.

But the euro made it very easy for them to be profligate, to borrow. Northern Europeans, and the Balts in particular, take satisfaction from pointing the finger at southern Europe and saying: you need to learn to behave. But we might need a debt jubilee like in the Old Testament and write some of this debt off. And then to think about how to go forward without debt dependence, because one can’t just always write off debts.

But there is another part of Alexander Hamilton. He published an important book with a very dull sounding title, “Report on Manufacturers” published in 1791, and gave it to the US Congress. In this volume, he made the argument that such steps were actually made on national security grounds. He said: we live in a dangerous world, we just had this Revolutionary War, let’s not forget that the British will probably come back and the French, who were our allies because they hated England, may hate us the next day. So, he argued, the US needed a national policy to encourage manufacturing. One of the things that we discovered from the Revolutionary War was that we couldn’t make the stuff that we needed to defend ourselves, France supplied 50% of our navy and lots of our armies, while we couldn’t supply them with what they needed because we just couldn’t make it.

Source: Alliance for American manufacturing

So the instrument he proposed is one we can consider today: the tariff. The US essentially put really high tariffs to protect American manufacturers. The argument made at the time was that it can make your manufacturers lazy because they might start hiding behind this tariff. But the lesson is that we must start thinking about ways of implementing it, because all successful countries have done this. They’ve all distorted the market in one way or another.

Did I hear correctly? The United States, this beacon of free trade, was successful because it distorted the market?

Yes. There is no such thing as a free market, it never happened. Initially, all industrialized countries distorted the market one way or another. The Germans did it, the Japanese did it in their own way. Distortion of prices has always been essential for developing countries. The Japanese make the most interesting case. In 1853, Americans sent a naval expedition to Japan with Commodore Matthew Perry. His job was to find a fuel station. The Americans wanted to trade with China, sell opium actually, and needed a fuel stop. And Japan was it. They were really isolated and got quite shocked when these Americans showed up and said: we’re going to buy coal from you, whether you like it or not. The Japanese did not like it and their response was fascinating.

Japan at the time had a very old, archaic culture still based on samurai culture. They saw the Americans as barbarians with really good stuff. And so they actually started a think tank. It was called the Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books (Bansho Shirabesho, 蕃書調所). The Americans came with steam power ships and the Japanese wanted that stuff. On his second trip, Perry brought a model steam locomotive train and assembled it on the spot, just to further show the Japanese what the Americans could do. The Japanese were impressed by it, they just were terribly unimpressed by the Americans.

Like the article? Support us here:

So what the Japanese learned was to follow what the Americans do, not what they say, because that often is a lie. And they followed the Germans and the Americans who both used state policy in different ways to develop. The Japanese just did it to an even greater extent and very successfully.

There’s no reason why a competent government cannot have these state credit institutions creating credit for the purpose of funding infrastructure that will create more wealth than the original cost of the credit.

Your Lithuanian deputy Gintautas Paluckas was right on target when he alluded to state development banks and state credit institutions. The problem with banks is that they’re not charities and so they don’t want to give money to people who need it. They want to give it to people who already have it, so that if they need to pay their loan back, they have the money. But how do you fund the people with really great ideas that don’t have money or collateral? Well, the German model especially has been to use state development banks and state credit institutions. And this way you’re also eliminating the rent of profit on lending, which makes credit more expensive, thus hindering development.

Wouldn’t that violate EU rules against state intervention?

The Balts are always very serious about following EU laws. Frankly, you should try and cheat a little bit when you can, because others do it all the time. I’m not saying you want a culture of cheating, but just learn where you can bend the rules. So Article 123 says you can’t have any state institutions creating money because that will undermine the European Central Bank, your authority for issuing the euro. Well, okay, but private banks do this all the time, they create money on computer keyboards. Of course, they have to then find ways of getting it back once they create it, the loans have to be serviceable. But they create money all the time. There’s no reason why a competent government cannot have these state credit institutions creating credit for the purpose of funding infrastructure that will create more wealth than the original cost of the credit.

This is something that economist and one-time advisor to the EC Mariana Mazzucato also says.

Yes, like Ha-Joon Chang, Mark Blyth, James Galbraith or Michael Hudson and others. All these people that have been somewhat influenced by the tradition of the late Hyman Minsky and all these kinds of heterodox approaches to money.

Thank you for conversation

Main illustration: University of Latvia

Taip pat skaitykite

-

The Interview: How to Occupy a University? The pro-Palestine Student Occupation of Ljubljana University

-

“In Slovakia the whole process is the same as in Hungary and Poland, but like on steroids, it’s much faster”. Interview with Tomáš Hučko

-

„ChatGPB and a half“: Qassem from Gaza – „You don’t destroy political thought by weapons”

-

Challenges of healthcare reform in Ukraine: on workers’ perspectives and struggles

-

Ian Parker: The Psy Professions, Pathology and Alternatives