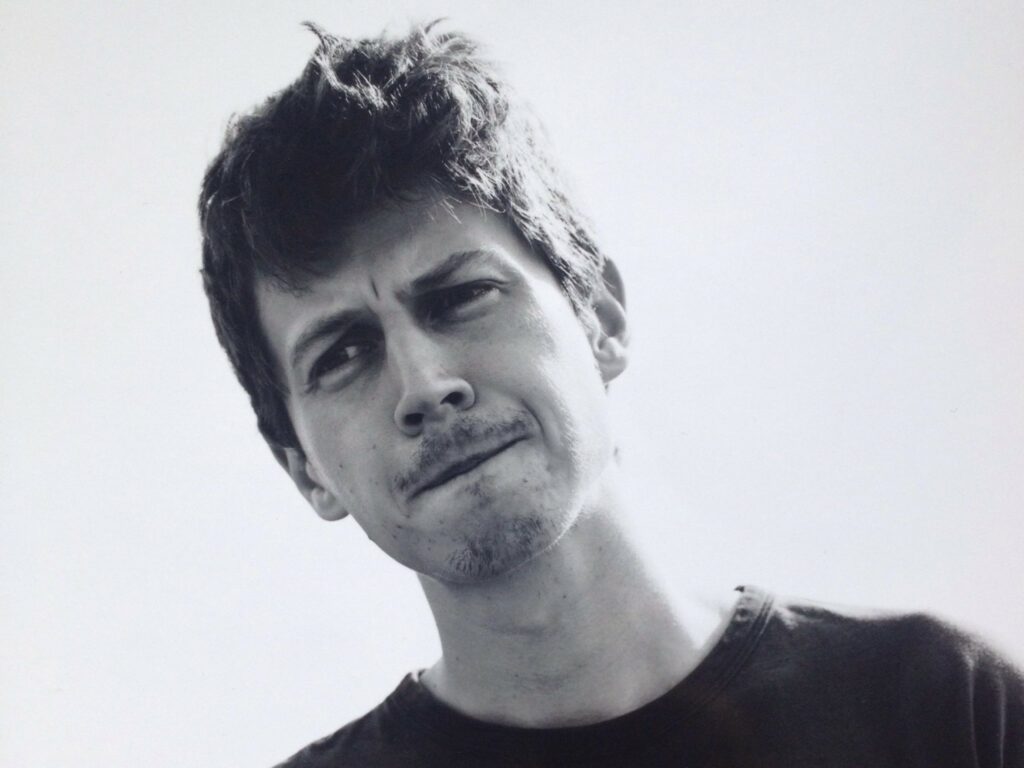

Karolis: We know each other from a meeting in Budapest when, representatives of different Eastern European left wing media gathered to form a network. I know you as an editor of Kapitál, but, how would you like to introduce yourself?

Tomaš: I cannot make my living solely as the editor of Kapitál. Therefore, I also work, broadly speaking, in a cultural sphere. One of my roles is translating books, including fiction and essays from English to Slovak. I write for several other media and quite often host discussions and cultural events. Essentially, my work revolves around culture. Usually, I piece together my monthly salary from five different sources.

K: So your salary is some sort of an assemblage of different activities.

T: Yes, I am somewhat of a freelancer.

K: Before we sat down for the interview, you mentioned that Kapitál is undergoing reconstruction. Could you tell us a bit about those changes and what brought them about?

T: Kapitál was founded in 2017 as a printed journal. During the first months it existed in print only. Then it went online. This has been going on for more than seven years now. Our aim was to explore larger topics each month and publish essays and long reads on such topics. And this is fine. But the target audience appeared to be limited with this kind of writing. So I decided that we should focus on reaching a broader audience by concentrating solely on online writing, aiming to be more responsive to current events. This would involve not only different formats and genres but also broadening the range of authors, including giving space to an older generation of leftists, left-leaning ex-politicians or diplomats. Thereby we want to try and create a platform where different leftist views can be talked about. As you probably know, and I believe this is the case in every country, the left is always fighting within itself.

K: True, the best fights are always internal fights.

T: Yes. I am not even sure if that is possible but I hope that there might be different voices from the left represented there [in the journal]. It should happen at the end of the winter, beginning of the next year.

K: And are there any political goals implied in this change?

T: Politically, it’s similar to what we have been doing. That amounts to the representation of democratic or non-conservative, non-nationalistic left as it is represented in parliament or by any political party.

K: I will surely want to come back to this topic of nationalistic left as I am very interested in the topic of nationalism in the region.

T: It’s a huge topic right now in Slovakia.

K: But I wanted to stop at the older leftist generation that you mentioned. This is something that, in my opinion, we lack in Lithuania. During the Soviet times, we didn’t really have any genuine attempts to reform socialism. Therefore, I wanted to ask you about the intellectual legacy from the period of socialism. Is there any legacy of reform socialism in Slovakia, and has it been rediscovered to some extent in recent years?

T: It’s not happening, although it could and should be. We still have some older socialist intellectuals, like Milan Šimečka, for example, or Antonín J. Liehm—who’s Czech, right? But the generation I’m talking about now is in their sixties and seventies. They are part of the group that tried to establish some kind of democratic left. The first party they founded was called the Slovak Democratic Left in 1990. They made attempts in politics, sometimes failing. Some were part of Smer – sociálna demokracia [Direction – Social Democracy] for a while, and many of them tried to support Hlas – sociálna demokracia [Voice – Social Democracy].

K: The party that was formed from Smer?

T: From the renegades of Smer, yes. These people are still legitimate even in the mainstream or in liberal media. Many of them, like Boris Zala or Peter Weiss, are now writing for liberal newspapers. I had a call today with Boris Zala—one of those most pronounced names of the 90s generation. He wants to participate in this new project and he’s also trying to establish some kind of new platform, a think-tank, where younger and older leftist intellectuals could produce something. So, there are at least some people who’ve tried to make these things recently. I’m not sure how it’s going to go but the discussion between the generations is not really happening or it’s happening only marginally.

K: I guess it depends on individuals, right? Because during my time in Budapest, I remember young folks very much admiring Gáspár Miklós Tamás. And one of the reasons why I asked about this is because to me it seemed that this rapprochement was in the air for the last decade. Just think of Bernie Sanders in the United States, Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom. So, it seemed like there was some sort of a coalition between different generations brewing. But then in Lithuania we simply don’t have such people.

T: We have only a couple. And from my observations, young people, those in their twenties, don’t care about the older generation.They don’t know them, they care more about queer rights.

K: Maybe at least they know Slavoj Žižek?

T: No, I think Žižek is not popular. I don’t know why. He definitely said something about women or something.

K: He says many things.

T: I like him, but I like older guys. But the problem is also that these older leftist intellectuals can be counted on one hand.

K: On the other hand (pun intended), what about cooperation with those older left-wing intellectuals from the Czech Republic. I mean is there still any Czechoslovak internationalism left? Do Slovaks still cooperate with the Czech left-wing intellectuals?

T: Yes. But more with those from the younger generation. There’s quite a lot of them there. The scene [in the Czech Republic] is much more vibrant than here in Slovakia. But they also have a couple of older guys. People who belong to those older generations either died or, emigrated long ago, like Václav Bělohradský. But their scene of younger left-leaning people in their thirties to forties is quite numerous. And we cooperate with them, of course. They have more leftist media than we have—Alarm, Advojka, Deník Referendum—to mention but a few.

K: And are these media tied to political parties or think tanks or are they independent?

T: Independent.

K: Then it’s many times more than what we have in Lithuania. One topic that I cannot avoid, relates to the fact that in Lithuania news about Slovakia is rare. The last thing covered was an attempt to assassinate your prime minister. Can you briefly reflect on how society came to this point? How it became possible that this attempt was made and what brought it about? Is the polarisation of society so big?

T: Of course. The polarisation is huge. And now the polarisation also comes with huge frustration of at least half of the population. I’m super frustrated. I’m not condoning violence, but in a way I understand why it’s erupting and exploding sometimes. Because the pressure is super high. What the government is doing right now every day is fucking amazing. Pro-democratic people and people from the field of culture and cultural institutions… you’ve been to the protest. They’re working every day just to save something. It’s very annoying and tiring.

K: Indeed, the last time we met was at the protest. That protest was a reaction to sacking a couple of heads of cultural institutions. This was initiated by the Minister of Culture, who is from the Slovak National Party, a smaller political partner in the governing coalition.

T: Yes, it’s a small party that barely made it to the government. The threshold is 5%, and they got 5.6% of votes. And what they did is an interesting story. How did this super nationalistic party manage to get a chance to enter the government again? They established a huge platform, bringing together the worst Youtubers and people from the disinformation scene to come to their ballot. That’s how they got those 5% and ten seats in parliament. But of those ten, only one was a party member, and that was the party leader. The rest are from the fucking Youtube.

K: So they hired alt-right stars.

T: Yes, like the Minister of Culture. She’s not a party member. She had a pro-Russian TV show on Youtube called TV Slovan, which was about being Slavic. The program was so popular that it got her elected and now she’s the Minister of Culture.

K: So some really fringe politicians made it into the mainstream?

T: Now they are politicians. Before all they did was owning an iPhone and having a TikTok or Youtube channel.

K: What about Smer and Hlas—the winners of recent elections, who replaced the previous government. I assume the current polarisation is increasing because of what Smer, Hlas and the Slovak National Party are doing while they’re in power. But how did the situation become so polarised?

T: It’s a long process, but I can tell you why they came to power.

K: Was it because of COVID and the war in Ukraine?

T: These events are part of the story. But the bigger problem is that when Robert Fico lost the elections in 2020, it happened just before Covid. He lost it because of the assassination of the journalist Ján Kuciak, and his fiancée. And the party that won the election wasn’t the party of experts or intellectuals. It was a super populist party, called the Obyčajní ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti [Ordinary People and Independent Personalities]. For years it was running on the anti-corruption topic. They went to power with another populist party that was very close to the far right, funded by this entrepreneur slash mafia guy. And then they were joined by a small liberal or neo-liberal party founded by the ex-president Andrej Kiska. The problem with this government was not that it was evil, but that it was simply very incompetent. Moreover, the country’s prime minister was an insanely egocentric man, unable to cope with his duties. It’s like giving power to a 12 year old. No wonder people were angry about how the government dealt with the pandemic and later with the whole Ukraine situation and so on. And Smer, which at first looked like a beaten guy, quickly and radically changed its rhetoric. They realised where the political points were and were able to grab them. The far-right rhetoric against immigration and immigrants, anti-Covid and pro-Russian positions were what won the party the election.

K: This pro-Russian sentiment is interesting. It is surprising and I am not able to understand where it is coming from? What are the roots of this sentiment? Is it some sort of a historical issue that brought the two nations together or is it something that was nurtured during the socialist period? Or both? How do you see this?

T: This is the question some analysts are trying to answer as well. I think there’s also a third explanation. It’s not so much about history. It’s more about the anti-Western sentiment. It’s more anti about being Western than pro-Russian. As you know, we’re not the only ones—there’s Hungary, Poland. The pro-Russian stances come from being Eastern European, and as Eastern European being unsatisfied with how the European Union works. Where on the map of the European Union is Slovakia? At the centre or on the periphery? What is the core and what are the fringes of the EU and how does it work? It’s also partly about respect or disrespect. I think that many Eastern Europeans feel and either consciously or subconsciously follow this anti-Western sentiment. And so where do you turn if you’re anti-Western? Russia is the answer. That’s why, in my opinion, many people are pro-Russian. Because they hate America.

K: Do you mean that there’s this dissatisfaction with being second-class EU members?

T: You put it very well.

[…]

K: I wanted to ask a question about nationalism and nationalistic left. Is it ‘nationalistic’ and is it ‘left’ when we talk about Smer? Because many times I feel that these labels are oversimplifying the picture. For instance, when we talk about Poland and look at their Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [Law and Justice] party some people would say that they were pursuing a leftist economic policy. While it is clearly a Christian democratic kind of welfarism. And when one looks at nationalism in Hungary in Poland, though I am not sure about the Czech Republic, then it can be seen that this nationalism is not this traditional nationalism directed against foreign countries or like minorities within your own country. Quite often, this nationalism attacks part of the majority. In Poland, for example, such rhetoric would include accusations against „bad” Poles.

T: Bad liberals?

K: Bad or liberal—Poles destroying the Polish nation from within. So it is a kind of nationalism that looks inwards. I would sometimes even compare it to an autoimmune disease. So how do you see this in Slovakia in general?

T: I would say that it’s very similar to what you described in these other countries. It’s aimed at internal enemies blamed for being internationalist, cosmopolitan, etc. Being cosmopolitan and liberal is the worst. Smer started using the rhetoric of liberal fascism a few years ago and got it quite popular in their part of the universe.

K: They employ this anti-fascist rhetoric as if they were true leftists, right? (laughing)

T: Yes, they’ve been doing this for two or three years now, I mean calling all the enemies of the ‘real Slovakia’ liberal fascists. That included the previous president, the liberal parties, obviously, the mainstream, the liberal and public media. All of them are labelled as ‘liberal fascists’. As well as all those who take part in protests. I’m not sure what it means, how they got there, but from this weird term, you can see the form of their nationalism, where being liberal is somehow compared to being fascist. […] That’s their biggest enemy right now. The nationalist tone and the conservative tone is not new but it has evolved. It wasn’t so pronounced seven or five years ago. Also it changed after the previous election. As I have mentioned, they changed the rhetoric. And now the question is not only how Smer evolves, because I think they are evolving very fast into the super conservative nationalist party. But Hlas as well is an interesting puzzle. Although they often agree with these nationalist strategies and PR stunts, they are not so radical in their statements. Therefore, the question is whether eventually they move in this direction as well or try to pretend to be some kind of democrats.

Consider supporting our work

K: I guess if they want to continue to exist in the Slovak political scene, they should think how to differentiate themselves from the other coalition partners? What about the economic policies of Smer? At least in the international media and in Lithuania, you read that Smer is culturally conservative and economically left. Is it like that though?

T: I cannot really tell you about their economic steps because they are not taking many. Since they came to power most of their energy comes to the judiciary system and culture.

K: And culture? So, they’re not trying to encroach on some important positions economically?

T: Not that we know of.

K: Why do you think culture is so important to them? Why is it a prime target? I mean this Kulturkampf, I sense, is going on. I have the experience of living in Hungary, where, as I watched the development of the country’s democratic system, or rather the destruction of the democratic system, this Kulturkampf took place, but only after the suppression of the free press, the free media and the subjugation of the judicial system. The conflicts needed to mobilise the public were on the wane, so it seemed that Orban needed to add fuel to the fire, hence the Kulturkampf. Why do you think that this step was taken much earlier in Slovakia?

T: In Slovakia everything happens earlier than in the other states. This whole process is the same as in Hungary and Poland, but like on steroids, it’s much faster. I really don’t know why they are doing it so fast. I don’t think anybody knows, they are in a super hurry.

K: They try to make the leap of modernization. (laughing)

T: In a few months. (laughing) But, as you said, the first steps taken in Hungary, such as the crackdown on free media and the judiciary, are the same here. They already control public TV and radio as well as the judiciary system. Our penal code was changed.

K: Could you describe these changes in a few sentences?

T: The time frame for dealing with previous offences has been shortened. So many of their crimes have now been absolved. Whatever happened ten years ago, we don’t care about it now. That’s one thing. Another part of the changes to the Criminal Code and the control of the judiciary now provides that virtually anyone can be exempted from criminal liability. This is what happened two weeks ago when they absolved the ex-prosecutor Dusan Kováčik who had been found guilty by several instances of the judicial bodies. He was lawfully put in jail, already in jail and they took him out of it. Officers found golden bricks for millions of euros in his house. He was so corrupted. And now he’s absolved. So they’re doing all of this and the Kulturkampf is here much faster than Hungary. It’s not a well thought strategy however. Huge part of the whole cultural war is [done by] the small party. And I do not believe it to be a coordinated or super sophisticated strategy on the part of Smer. They just go along with it. And when you listen to Fico and his speeches after the assassination, you can see that he really likes to provoke now. He has always been a provocative politician, but today he is even more provocative. When we watch those videos, we recognise the guy. We have been looking at him for twenty years, and you can see that he enjoys it.

K: Is he full of vengeance and it’s a tour de force that he is having, right?

T: Yeah, totally.

K: Do you see any possible hope for change? And if yes, where would you look for that?

T: This is the worst question, always.

K: This is an obligatory question, you know. (laughing)

T: Yes, I had a couple of interviews last month. It always ends with this question. I’m not very hopeful right now, I must say. My wife wrote an article about what’s happening in the sphere of culture. And partly it’s quite a pessimistic article because she compared it to what was happening in Poland and Hungary. She talked to some people from those countries and they said „This was happening and we couldn’t stop it. Regarding culture, we did what you are doing now. We held protests, wrote petitions, organised discussions, etc. And nothing really helped.” And you can somehow see the similar results in Slovakia. You saw the protest, and it’s nice. But it doesn’t bring back the institutions. After the protest, the government’s rhetoric became even more radical and harsh. During the last few days the government, including Fico, were attacking a civic institution called Milan Šimečka Institute. It’s named after the philosopher Milan Šimečka. The Institute was established after his death. But the leader of the Progressive party, the main opposition party, happens to be Šimečka’s grandson. And although he has nothing to do with the Institute, except the same name, the Ministry of Culture held a couple of critical press conferences about it. Fico had videos where he’s asking this young Michal Šimečka, the head of the party, to resign from his post in the parliament because the institution receives money from the arts council. But this it’s absolutely legitimate. We work with the Institute often. They are publishing books, organising a festival for migrants and for minorities in Slovakia. They also organise a lot of educational workshops for Roma kids, which makes the Institute a kind of an educational platform. And now the government is attacking and threatening them that they will not get any more money from the state. Because they are connected to this grandson. It’s really crazy.

K: There’s a saying that if you want to beat someone you will find a stick.

T: But this stick is so crazy. This is like the craziest stick. And it’s really depressing. That’s why when you ask if we are hopeful or not, I should answer no, not during these days. If you live here and you know the details, then you know that what is happening has nothing to do with reality, logic.

K: Craziest stick, I think you just gave the title for this interview (laughing).

T: So we’ll see how it goes with this institute. I hope they will survive because they’re doing great work. But this is Fico in full rampage, this is the stick he is using right now. He’s recording videos on how „we must stop these liberals getting money from the state.”

K: So he’s slowly turning into this Youtube right-wing influencer.

T: He’s already there, he’s part of them already. I have one more funny story connected to Youtube far videos. There is a guy called Daniel Bombic. And he’s, I think, an open Nazi. He has his own TikTok or Telegram channel where he talks about all sorts of Nazi stuff. Meanwhile several international police institutions are looking for him. Several international warrants have been issued for him by the FBI or CIA. He’s hiding because several countries are looking for him for his Nazi connections and all of this. And now listen to this—while hiding he’s doing his show online and people from ministries, including ministers from the government, come to his show to talk to him. The Minister of Interior was a guest on his show!

K: Very well-linked ministers.

T: That’s so bizarre I cannot even explain it. […]

K: It is surprising that to preserve power Smer and Fico went to take such a fringe position.

T: But it worked.

K: I wanted to ask this earlier. Some years ago everyone was shocked about the emergence of Marian Kotleba and his neo-Nazi party. What happened to him, is he still active?

T: He’s active, but he’s been marginalised.

K: Did the success of Smer have something to do with this marginalisation?

T: Of course. Smer drained a lot of his voters. Also his party split and a new party called Republika was founded. They are Nazis in nice suits.

K: Okay, probably the last thing that I want to ask is about Ukraine. Some time ago I read that the Slovak government decided not to send more weapons to Ukraine. On one hand, they don’t really have what to send. On the other hand, Fico said that if some private companies want to do that, the government would not mind. And there are some private weapon manufacturers linked to one of the ministers. There was some sort of cooling down in Slovakia’s stance towards Ukraine. But then I read that ordinary people donated 2 million euros for Ukraine during an aid campaign. So what’s the situation with the help for Ukraine? Is the society split into two parts over the issue, or is it that it’s only the government reluctant to provide help?

T: There are two sides. First, as you mentioned, the government’s position is somewhat unclear. Fico says one thing here, the other thing in Brussels, then he says something different to the Ukrainian prime minister. So it’s very difficult to get their position. It’s different, in different contexts. As you said we are not providing guns, but we can still sell them. On the part of the people yes, the the collection of money was very successful. There were about 2 million euros donated. However, I would say that sympathy for Ukraine is only one thing fostering the sentiment of collecting money for Ukraine money. This was also a protest move against the government. Half of the population doesn’t agree with the government and for them it was an opportunity to demonstrate their protest and to show the government that the money could be collected without them. At least I felt it that way. A really huge part of the sentiment comes from this. But that’s fine, we got the money. Yet, the country is polarised on the issue. It’s really 50-50. Yes, a huge sum was collected, but if you look at the commentaries on social media, there are many people who hate it.

K: We started talking about Ukraine, and I think that there are two questions that go hand-in- hand here, namely, Ukraine and Palestine. Is it like in many other countries where general sentiment is very much pro-Israel? Or maybe Slovaks are more supportive of Palestine?

T: No, I would say it’s very similar to other post-communist countries in the region. Perhaps the Czech Republic and Czech society are even more pro-Israel than their Slovak counterparts.

K: Perhaps Smer is a bit more pro-Palestine? (laughing)

T: It’s weird, but it is. There was this very nice pro-Palestinian protest a month ago. Quite a lot of people came. But you could meet some people there from Smer too, for example, that are ashamed to be walking next to them. But the sentiment is similar. There are supportive voices, but there’s not many of them. The majority of mainstream Czech media is very pro-Israel, and that’s very similar to Slovakia. There are only a few leftist media outlets, Kapitál is one of them, that show some sympathy towards Palestine.

Taip pat skaitykite

-

The Interview: How to Occupy a University? The pro-Palestine Student Occupation of Ljubljana University

-

Muskas, Trumpas ir broligarchų naujasis hiperginklas

-

Arundhati Roy: „Jokia propaganda pasaulyje negali paslėpti žaizdos, kuri yra Palestina“

-

Rūpestis be pabaigos: apie kairumą ir kenčiančias aukas

-

Ar kurjeriai bus įdarbinti? Austrijos atvejis