You can also listen to this article:

Šį straipsnį galite skaityti bei klausyti ir lietuvių kalba.

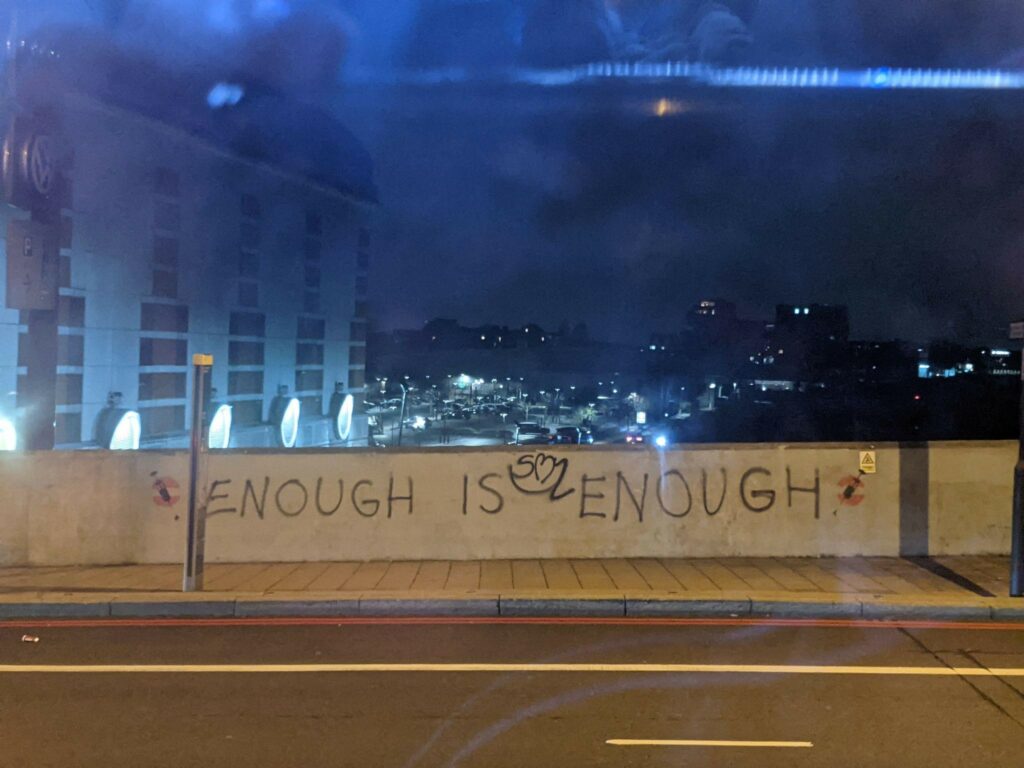

We have known about the worsening mental health crisis for a long time, with the word “epidemic” rightly used to describe the spread of mental illness. We are now more open about our personal mental health – and yet, in an age of social movements such as the Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter, we have no such movement for mental health. Why is there no political activism around mental health? What can we do to spark the movement?

For the last 13 years, I have studied and worked in mental health. Currently I work as a school counsellor/child and adolescent psychotherapist in London. Lockdowns gave me a chance to reflect and start conversations about the mental health crisis with many of my friends and colleagues. Let me explain why I think that the mental health discourse is severely underdeveloped and what challenges lie ahead for those working in mental health.

The Underdeveloped Public Discourse of Mental Health

As a social movements researcher Deva R. Woodly notes, it is only through public discourse that we can open the possibilities of political change. However, within the mental health sector there is a lack of activism that has the power to influence public discourse and, in turn, government policy.

Currently, the public discourse around mental health is severely underdeveloped. For example, conversations around mental health tend to focus only on the personal responsibility of the individual. By contrast, Extinction Rebellion’s call for collective action goes beyond urging individuals to recycle and use less plastic. Likewise, the public discourse on mental health should go beyond urging individuals to think positively, take yoga classes, eat healthily, exercise more, and so forth. Mental health illnesses do not appear in a vacuum. No mental illness was caused by a lack of yoga. The narrative of the public mental health has to become systemic.

We need to popularize psychological knowledge on how mental health problems are passed from one generation to another. For example, we have known for a long time that infants will only learn how to cope with stress if caregivers are soothing and in tune with their children. We know that 30-40% of children grow up with an insecure attachment style, which essentially means they do not feel emotionally safe in this world. We know that attributes such as violent behaviour and self-control are passed down from one generation to another. We are able to look at the intergenerational transmission of trauma psychologically, epigenetically, economically, and so on. Such systemic understanding of the mental health crisis can be translated into concrete targeted programmes for change.

An example of a long-term and efficient investment in mental health is the parent and baby mental health clinics advocated by the psychotherapist Sue Gerhardt – such clinics support and enable parents to better recognise the needs of their infants. If such services were available to everyone, in the space of a generation the prevalence of mental health problems could be significantly reduced. This is one of many ideas that could take root in the public discourse.

In fact, we are not just seeing a lack of the utilisation of psychological wisdom – we are seeing an active misuse of this knowledge. As shown by Adam Curtis in his documentary series The Century of the Self, which shows how psychological knowledge has been used to stimulate consumerism. Similarly, the documentary Social Dilemma reveals how social media is deliberately designed to be addictive, while research has shown how social media negatively impacts the mental health of teenagers.

Psychological knowledge can be used for negative or positive ends. It can be used to generate financial benefit through exploiting trauma, or it can be used to prevent and heal trauma. The solution, I believe, is an informed public discourse that actively challenges the profiteering that causes mental illness.

The Challenge for Mental Health Professionals

Since they have the right knowledge and a capacity for empathy, mental health specialists are the best candidates to spark a mental health movement. However, workers in this field tend to lack organisation. This needs to change, because no other group in the western world has the credentials to advocate for change in mental health. No other group is in a better position to digest this infinitely complex problem and articulate it in understandable language. Moreover, political activism is compatible with the integrity, courage and ethics that the mental health field stands on. In the words of philosopher Alan Watts: “The therapist who is really interested in helping the individual is forced into social criticism.”

Mental health workers can be socially critical, but this happens mostly in a private and gentle way. We lament the under-funded, short-term-oriented mental health system, but we tend to stop short of collective political activism. One of the influential contemporary psychotherapy personalities, Graham Music, rightly noted that for us, psychotherapists, to engage in a professional activity outside the comfort of our consulting rooms is like for moles to leave their mole holes.

In fact, the most revealing evidence for how mental health workers struggle to engage in political activism is how we neglect our own rights. For example, most school counsellors in the UK are technically self-employed, although we cannot set our pay rate or when we work. As a result, we have a situation where committed professionals, often working for years in the same institution, have no holiday pay or sick pay. The employment status of school counsellors is a serious and unattended legal issue. So we must face the question: How can we learn to advocate for others if we are already struggling to advocate for ourselves?

One reason is the subculture of the field, which includes high levels of privacy and solitude, and even loneliness. For example, a private psychotherapy practice is an isolated profession in which contact with colleagues can be minimal. Furthermore, psychotherapists and psychologists who live in small communities can be particularly lonely as they seek to avoid non-professional contact with clients, meaning they will avoid going to the local pub or community event.

A promising space in which mental health workers could connect is online. However, many working in mental health actively limit their online presence, largely because therapists and psychologists typically don’t want their personal information to be accessible to existing or potential clients. However, in this day and age, online spaces are vital to cultivate togetherness and organise ourselves. In our times the public discourse cannot be changed without vigorous online activity.

Being versus Doing

There is another issue that I think needs addressing: the beliefs widely shared by mental health workers tend to be at odds with activism. A key concept in the canons of psychotherapy/counselling, psychology and arguably the western approach to meditation is that of “being versus doing”. The implication is that being is more important than doing.

Being is about openness and acceptance of arising experiences, feelings and bodily sensations. Experiences are neither good nor bad, so there is no need to engage in doing, i.e., no need to fix, change or escape our experience. In a world of frantic activity – of doing it better, longer, faster, higher, richer and bigger – being is a refreshing change of perspective. I love being a part of a culture where being is nurtured.

However, “versus” suggests an unnecessary opposition between being and doing. From this binary stance, political activism is likely to be dismissed as undesirable doing. Indeed, in my own professional context, I have struggled to find validation for the outward-facing, politically active part of myself.

Perhaps the world has suffered for so long from self-indulgent and destructive manifestations of power that we, proponents of psychological and spiritual growth, have come to romanticise an underdevelopment or aversion to activism, leadership and outspokenness. The ideal of wisdom is more typically seen in the person who lives on top of a remote mountain pondering Oneness rather than the one who tries to change the reality.

As I write this, I feel my anger arising. Of course, I can look inwards – I can get in touch with how I experience this anger in my body – and I can get in touch with the feelings that reside underneath my anger. There is much to learn from exploring our feelings but there is no necessity or virtue in not acting. We must both allow our experience to unfold in the present moment (being) AND translate our feelings into action (doing).

Patinka straipsnis? Galite padėkoti čia

In an interview with Therapy Today, Psychotherapy and Counselling Union representative Richard Bagnall-Oakeley said: “Sometimes our wish to remain in a detached, reflective ‘observing I’ position can be defensive.” The brewing mental health crisis is a growing challenge to these defences. For example, the waiting times for child mental health services has gone up to a year and even more. It is challenging us to question the binary perspective of being and doing. It is challenging us to meet reality and respond to it with courage. It is provoking us to balance and integrate our Being and Doing. Remaining in our mole holes or meditating atop mountains will not achieve this. It is time for ground level action.

The mental health movement needs to address a lot of issues. We need to ignite a healthy public discourse that facilitates political opportunities and the involvement of the wider public. We need to promote protection for workers in highly stressful, burnout-prone settings, such as schools and hospitals. We need to focus on breaking the transmission of trauma between generations. We need to resist austerity policies. We need to regulate psychologically unsafe cultural products, such as social media.

But, first and foremost, we mental health workers need to come together. We have to find online and physical spaces to gather in. I know that doing this is possible and effective, having myself initiated discussions about political activism with colleagues that generated a mutual sense of validation and empowerment.

Pauliaus Garmaus iliustracijos

Taip pat skaitykite

-

The Interview: How to Occupy a University? The pro-Palestine Student Occupation of Ljubljana University

-

“In Slovakia the whole process is the same as in Hungary and Poland, but like on steroids, it’s much faster”. Interview with Tomáš Hučko

-

„ChatGPB and a half“: Qassem from Gaza – „You don’t destroy political thought by weapons”

-

Challenges of healthcare reform in Ukraine: on workers’ perspectives and struggles

-

Ian Parker: The Psy Professions, Pathology and Alternatives

1 thought on “The Pending Movement: What Can Mental Health Workers Do?”